Sunday 21st July – a leisurely day around Stromness

We have mentioned before that many coastal communities have developed their own traditional boats over the centuries. This is a Stromness “yole” – albeit with the addition of a modern outboard

After a leisurely start we find the local information centre to find out how to get about Mainland Orkney. This being Sunday things seem to be shut or limited opening here so we sort out a full sightseeing day tomorrow and decide on a day around Stromness and a walk along the coast.

“Flattie” racing in Stromness harbour. This girl took her dog with her! Flatties are traditional flat-bottomed boats that children and teenagers learn to row around Stromness harbour area. The growth in the size and amount of ships using Stromness must limit this activity these days. The local golf course seemed to attract far more youths on this particular Sunday!

A passer-by tells us that this week is “Shopping Week” in Stromness – their carnival week. (The information centre is so clued up that they did not even have any information on this event 100 yards from their door!). This afternoon there is “flattie racing” for teenagers in the harbour. A flattie is the local flat bottom rowing boat young people learn to row in at Stromness so we take our lunch to watch from the harbour wall. There don’t seem many takers and there is little fanfare but a few youths take part. We decide to walk on after a couple of people complete their timed circuit round the harbour. (Later we find a lot of youths playing golf with their dads – maybe Lee Westwood leading the Open is more inspiring to them).

Mrs. Humphrey’s House – a temporary hospital for scurvy ridden whale men who had been trapped in the ice for months working fo the Hudson Bay Company

We walk through Stromness’s main street – a collection of houses, pubs shops and churches constructed from the local sandstone. Many of the houses have been rendered, mostly in the pebbledash much used in Scotland, which is a pity as it is rather drab. The road is often narrow with flagstones and cobbles up the middle with traffic and pedestrians mingling. There are information plaques along the route as Stromness has various claims to fame, many relating to it providing many people to work for the Hudson Bay Company (HBC) in Canada. Stromness is celebrating the 200th birthday of Dr John Rae from the town who worked for HBC and made the final discovery of the North-West Passage. Unlike the other great Victorian explorers, he seems to have been shunned by Victorian society as he “went native” (befriending and imitating the Inuit and learning much from them) and also reported that the ill-starred Franklin expedition seeking the NW Passage resorted to cannibalism before freezing to death – something which, although later proved to be true, ran against the Victorian notion of a heroic death.

Although interesting in its way, Stromness is not particularly attractive other than its main street (which is a conservation area) and there is a limited amount of interest to (or it seems in) visitors.

We walk on round the headland on a good path past the Hoy Sound and Hoy Mouth towards the open sea.

Scapa Flow was an important naval base in both World Wars so there are inevitably remnants of defenses, such as this search light station overlooking the Sound of Hoy entrance to Scapa Flow. A rapid fire gun emplacement, control tower, generator house and encampment completed this group of buildings.

We pass the remains of WW2 defences, including a generator shed, searchlight post and gun emplacement. Across the Sound we can see a similar establishment on Grimsay, compete with control tower. The Hoy Sound was one of two entrances to Scapa Flow – a great inland sea that was the base in the north for the Navy in both world wars. We found much more about this aspect later in our travels around the Orkneys.

A WW2 gun control tower on the island of Grimsay overlooking Hoy Sound at the entrance to Scapa Flow next to Low Hoy lighthouse. The mountains on the island of Hoy are behind.

Sandstone pavement at low tide off the island of Mainland, Orkney. The Mouth of Hoy and part of the mountainous island of Hoy in the background

John walks on round the coast to view the wave energy test site for the European Marine Energy Centre (EMEC). On his way he passes the house of the last protestant bishop on Orkney (of which more tomorrow).

The European Marine Energy Centre (EMEC) is based at Stromness. A wave energy trials area is located on the west coast of Mainland Island with several devices on test. Here two of the support vessels are returning from the trials area via Hoy Sound against the back drop of Hoy island, the most mountainous of the islands. The Devonian sandstone “pavement” formation in the rocks in the foreshore is typical of this area of the Mainland Island

The UK is regarded as the country within the EU that can most benefit from wind, wave and tidal energy. Wind energy is being rapidly developed (witness the huge number of wind turbines being installed) but wave and tidal energy are in their infancy, being largely at the research and development stage. The Orkneys are well placed for wave and tidal energy, being on the Pentland Firth (with one of the greatest tidal flows in the world) and being open to the waves from the north-west Atlantic. EMEC was set up on the initiative of the UK Government and is headquartered at Stromness with a wave energy test site at Billa Croo on the west coast of Mainland and a tidal test site on Eday. So far about 6 different wave devices from the UK and other countries have are or about to be tested with the British “Pelamis” wave snake being the first device to generate electricity into a grid system (in 2004). We saw some of the devices on the shore awaiting installation and the installation vessels in the Sound of Hoy on our walk. A new quay was also under construction at Stromness to support this work. We could see the Pelamis device out to sea in the distance on the walk.

Cattle farming is big on the Orkneys – as is some of the live stock. Anyone know what breed is chap is?

The walk took us through a lot of farmland. There seems to be little arable land in the Orkneys, although there was much hay and silage making in evidence. However, they are big on cattle and sheep rearing. The land is generally undulating rather than mountainous (with the exception of Hoy which is mountainous) with lush looking fields with plenty of stock in them. The local papers had stories of the dairy farmers being hit with low milk prices so no change there – perhaps beef farming is more remunerative. On one island (North Ronaldsay) the sheep have adapted to eating the seaweed – apparently it gives a tangy flavour to the meat!

The house built for the last protestant bishop of Orkney at Breckness over looking the Sound of Hoy in the 17th century

A detail in the ruined bishop’s house at Breckness – an oven perhaps? The stonework is noticeable better quality than most other buildings in the vicinity.

On his walk John came across the house built for the last protestant Bishop of Orkney in the 17th Century – now in ruins.

Back at Sundart John finds a loose little wire that had been stopping the radio linking properly to the GPS. (Our radio is a digital type based on the GMDSS system. The radio is linked to the GPS so the boat’s position is always known; in the event of an emergency (mayday) the radio automatically sends the position with the distress signal).

We eat on board and enjoy the Sunday paper (which only arrived in Stromness at midday – such is island life).

Monday 22nd July – Sight seeing in Mainland, Orkney

The local lifeboat gets a Sunday morning clean, ready to transport the local Shopping Week (Carnival) Queen the following day. This is a Severn Class lifeboat – the largest type built & used by the RNLI and stationed at ports with the heaviest weather and most open seas. Powered by two large Caterpillar motors, these boats can cruise at over 25 knots – but don’t ask about the fuel consumption or costs!

At last – a pipe band! At the Stromness “Shopping Week” awaiting the Shopping Week Queen coming to be crowned via the lifeboat

We do a quick bit of shopping for essentials, passing the preparations for the crowning of the “Shopping Week Queen” and the pipe band to serenade her.

We then catch the double-decker open top tour bus that goes round much of the island, visiting some of the main sights. There is a good travel deal – £8 for all day, hop on and off any of the island buses. The bus is full as it has already stopped at the capital, Kirkwall, and filled up with passengers off a cruise liner so we have to sit at the back on top in the open air. As we board an American lady totters off the top deck complete with oxygen trolley! The open top is great until the driver decides he is behind schedule and puts his foot down – over 40 mph is a full-blown severe gale when riding on an open top! Perhaps we should have borrowed the oxygen trolley. We don’t hear his commentary but arrive some what wind-blown at Skara Brae, the first stop and stagger off the bus. At least the scarecrow hair and odd hairless patches support our claim for concessionary tickets.

Modern mock up of a Skara Brae house with tunnel access passageways, primitive doors and turf covered roof (much like the roofs of traditional Skandinavian houses).

Modern mock up of the houses at Skara Brae. This is the living area with hearth in the centre and dresser behind with a hiding place for valuables in the wall.

Orkney has the highest concentration of prehistoric sites anywhere in the UK (and probably of most places in the world) with more being discovered to this day. Skara Brae is one of the must-see places in the UK. It is the best preserved Neolithic village in Northern Europe. It was discovered by accident in 1850 when a storm blew the sand off the top of the Neolithic village to reveal some tantalising structures. The Laird of Skaill and landowner, William Watt, was intrigued and started to excavate to uncover four compete houses and amassed a rich collection of objects. In the 1920’s the site was taken into state care and Gordon Childe, the first Professor of Archaeology at Edinburgh University, was given the task of excavating and preserving the village. Childe was keen to ensure it was well presented to the public and made a painstaking excavation of the site. In the 1970’s further excavation was undertaken using new techniques. A recent survey has shown that there is a bit more of the village buried under the sand dunes which may get excavated in due course. One issue that has to be resolved with each dig is that the village developed over many years with newer houses being built over older ones, so the depth of excavation is often a moot point.

Skara Brae is situated next to Skaille Bay. When the village was built the sea would have been along the line of the mouth of the Bay. A great storm in 1859 blew away the layer of sand that had been covering the top of the village. The on-lookers are walking along the top of a sea wall that has been built to protect the site from coastal erosion.

Later period house from about 3500 years ago. Stone beds each side, fireplace in the centre and stone dresser on the far side.

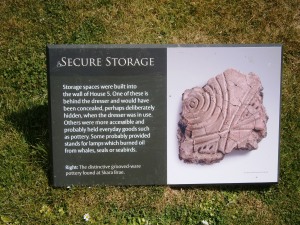

The settlement at Skara Brae dates back nearly 4500 years. There is a wonderful time line along the path leading to the site along which one passes stones marking the Aztec, Mayan and Egyptian civilisations (including the building of the pyramids), Jesus Christ and many other historical points before arriving at the village and 2500 BC. A reconstructed house at the outset sets the scene and is complete with stone furniture, beds and doors that could be closed which gives an immediate impression of homely comfort and a standard of living that probably exceeded that enjoyed by 19th century crofters. The houses are partially sunk in the ground with “midden” (refuse) around the outside to insulate and give stability to the stone walls. Sunken passages link the houses.

The settlement at Skara Brae dates back nearly 4500 years. There is a wonderful time line along the path leading to the site along which one passes stones marking the Aztec, Mayan and Egyptian civilisations (including the building of the pyramids), Jesus Christ and many other historical points before arriving at the village and 2500 BC. A reconstructed house at the outset sets the scene and is complete with stone furniture, beds and doors that could be closed which gives an immediate impression of homely comfort and a standard of living that probably exceeded that enjoyed by 19th century crofters. The houses are partially sunk in the ground with “midden” (refuse) around the outside to insulate and give stability to the stone walls. Sunken passages link the houses.

The actual houses are well-preserved. Some are now open to the elements to be viewed from raised walkways whilst others have been re-roofed with turf roofs to protect the inscriptions and artefacts within.

Quite apart from the construction of the houses, numerous questions arise including how did these people get to these islands across a difficult stretch of water, together with their families and animals and why did they come in the first place? Our guide suggested the climate was warmer which would have helped (so global warming is not new!) but more questions are asked than are answered.

Skaille House – next to Skara Brae and an elegant example of 18th Century living at the top of the hierarchical tree on Orkney

The site also includes Skaill House, the old laird’s home, which is a delightful glimpse of how the better off lived here in the 19th century.

As the bus is running late we have to hurry a bit which is a pity but there is much more to see. We would not make good tour bus customers!

The Ring of Brodgar. Originally around 60 standing stones in a perfect circle within an area rich in bronze age burial mounds.

Next stop is the Ring of Brodgar, roughly in the middle of the island between the large fresh water inland lochs of Stenness and Harray.

This is a ring that probably consisted of over 60 standing stones set on a small hill dating from the Bronze Age (around 2000 BC). As with all of these prehistoric rings no-one really knows how they were used. This one still has many of its stones standing (although at least one has been felled and split by lightning in modern times). The ring is surrounded by a ditch and is set amidst numerous burial mounds. Once again, the sheer scale of what the ancient builders achieved is remarkable, with stones being bought a long way then stood up in a near perfect circle. There must have been a high degree of organisation amongst the local people to have achieved this.

The Ring of Brodgar is linked by single standing stones over a mile or more to the smaller circle of Stenness, where far fewer stones remain standing.

Not far away is the burial mound of Maes How where carefully constructed burial chambers were made, covered by an earth mound. Access is limited so we were unable to visit this site. Earlier visitors include the Vikings, who opened and robbed the tombs and left their carved graffiti on the walls – which has now become one of the largest examples in Europe of Viking runic script!

Also nearby is the latest archaeological site – Brodgar Ness – where a dig is in progress using trained volunteers to uncover and record another Neolithic village. The quantity and quality of these sites is quite remarkable.

The Strynd Tearoom, Kirkwall – rejuvenation after the open top bus tour and excellent home cooking by the three young people running it.

The bus finally deposits us at the capital, Kirkwall, after a further perfect storm on the open top deck in the Orkney mist! We recover by seeking out a delightful little tea shop in a side alley off the main street which is run extremely well by three twenty-something year olds who can cook and run an excellent establishment. We recover our composure over a delicious bowl of home-made soup and buy cakes for later sustenance.

Having recovered we decide to seek out the Highland Park Distillery which is the most northern whiskey distillery in the UK located on the outskirts of Kirkwall. A mile and a half later up a hill we find said distillery in time for the scheduled 3 o’clock tour only to find that a cruise ship has fully booked the tour. We plead our case and after being mollified by a shot of 12 year old single malt whiskey and a film show on making their product they magic up our own personal guide – the amiable Chris. Tremendous! Chris immediately plies us with 18 year old single malt whiskey before taking us on the tour. This is more like it!

Mash tuns and filter vessels. Our amiable and accommodating guide Chris explained everything in excellent depth.

Copper stills. Two to make the first distillation, two for the final one. They are normally padlocked when in production by Customs and Excise.

Whiskey maturing in oak barrels. 2% is lost by evaporation – the “angels share”. Armour plated glass separates us from the product!

A brief description for those not familiar with whiskey making. Most distilleries started as illegal stills that became legal (in this case 200 years ago). Scotch whiskey basically involves making malted barley (i.e. selected barley which is germinated under control to convert the starch into sugar in the seeds of barley). This is then dried and roasted in a peat fired kiln to impart the characteristic flavour before making beer out of the malt. Batches of 30000 litres of 8% alcohol beer are made from which the liquor is separated from the barley (the spent grains being fed to happy cattle) and is then distilled twice in copper stills to end up with around 4500 litres of raw whiskey. At that point the government taxes the distillery. Unsurprisingly, the distillery is keen not to lose a drop thereafter!

Whilst all this is going on, there is the saga of the barrels. Whiskey is matured in oak barrels that have previously been used to make other liquor – in this case sherry – that helps smooth and flavour the whiskey. The distillery owns Spanish and American oak woods from which the barrels are made. These are then provided to sherry makers who typically use the barrels for two years before returning them to the distillery to be filled with whiskey ands left for…ages. About 2% of the whiskey evaporates through the oak – the angels share.

There are a number of surprising facts that we learnt. Firstly, it is not always clear exactly what the whiskey will be used for when it is laid down. Whiskey fashions change and the distilleries feel they need to keep customers interested so they will develop different types of product as they go along. Thus 40 years ago only about 5% of Highland Park’s output became single malt whereas now the vast majority goes into single malt. There is a certain amount of risk taking nevertheless: for example keeping whiskey for longer periods to develop and satisfy different markets assumes that there will be the disposable income to buy these products when they are ready.

A second surprising fact is how few people work at a distillery given the thousands of litres produced each year. Highland Park employs just 20 people (some of whom are on shift) plus 9 guides such as Chris.

A third surprise is that the distillery owns and operates most of its chief inputs including the moorlands it cuts its peat from on Orkney, the oak forests for the barrels and the two burns (streams) and their sources where the water comes from. It also controls the barley strain (tartan by name of course!) and how it is produced and shares the bottling plant with three other distilleries in its group.

We depart Highland Park clutching our purchases and well impressed by their service (and of course product!). A bus comes by so we hail it and ride back to town. (The buses here operate on a “hail and request” basis as there are few bus stops. This is a terrific idea as people often get collected and dropped off at their front gates if the bus route runs that way and it is safe to do so).

St. Magnus’s cathedral, Kirkwall. Largely constructed in the Norwegian period, then passed to the protestant community and finally the Church of Scotland.

Back in Kirkwall we enjoy our cakes previously purchased from the youths, then visit St Magnus Cathedral. This is a 900 plus year old building, constructed from warm red sandstone in the Norman style (rather like an enlarged version of the Parish Church at Melbourne).

The nave, St. Magnus’ cathedral with massive sandstone columns and arches in the Norman style dating from the 11th Century

It was originally started when Orkney was a Norse Earldom and as Orkney was owned by Norway it came under the Diocese of Trondheim. When Orkney passed to the Scottish Crown in 1468 (of which more tomorrow) it started being used for protestant worship until the last protestant bishop left in 1688 when it became the property of the Church of Scotland, where it remains. It’s a wonderful building and well worth the visit.

After the cathedral we pass by the ruined Bishops Palace but that is now shut.

We await our bus over a cup of tea in a nearby café-cum-art and craft shop selling (amongst many things) Fair Isle jumpers. Yvonne tries some on but at over £100 a go she decides against one. We discover that Kirkwall have a town football game on New Years day called “Ba” a bit like the Shrove Tuesday game at Ashbourne, complete with “Uppies” and “Doonies”. It seems these games were popular in many British and French towns but only a few retain them, Jedburgh and Workington being others. The game has remained popular and overcome official suppression. Shops are boarded up and gates barricaded but it remains a great public event with typically 200 players and many more supporters and onlookers.

Wearily we find the bus home (a completely enclosed design thankfully) and pass by many of the sites we have seen today. It’s been a great day out and yet we have seen only a little of what the Orkneys offer.

Tuesday 23rd July – Scapa Flow and St. Mary’s

We decide to sail eastwards across Scapa Flow to anchor off the island of Lamb Holm to visit the Italian Chapel. The weather is rather grey and misty as we set off down the Hoy Sound and into Scapa Flow. Scapa Flow is a natural inland sea, bounded by the island of Mainland on the north and various islands round most of the other three sides. It is big – around 125 sq. km – and was used by the Royal navy in both World Wars for their fleet.

It is also famous for being the site where the German Battle Fleet was anchored after the Armistice after the end of WW1 whilst the reparation negotiations took place. These dragged on so much so that the German commanders feared they would break down so rather than leave the fleet in British hands they scuttled the whole fleet whilst the British Fleet was out on exercises. Many of the smaller vessels were subsequently raised by a scrap metal merchant and broken up for their scrap value but around 8 of the larger vessels were left on the sea bed and stripped of their non-ferrous metal and armour belts. The wrecks are apparently well-preserved and are a top destination for divers.

As we tacked down Scapa Flow we passed over the wrecks off Cava Island, the depth meter registering momentary sharp reductions in depth.

At the start of WW2 block ships were sunk between various islands in the east to block off access to Scapa Flow by German U Boats but they were not enough. On a particularly high tide a brilliant German commander manoeuvred past the block ships by Lamb Holm and managed to sink the battle ship Royal Oak with the loss of around 600 lives before escaping. Our route eastwards also took us round the Royal Oak wreck off Scapa Bay, which is now a war grave and a prohibited area.

As a result of the sinking Churchill ordered the construction of four permanent causeways to link Mainland, Lamb Holm, Burray, Glimps Holm and South Ronaldsay. These took nearly three years to complete, including linking roads across the top and are now an integral part of the infra-structure of these islands, improving their access and prosperity. The Churchill Barriers were constructed by the contractor Balfour Beatty with a considerable amount of labour being contributed by Italian prisoners of War who had been captured in North Africa. The enterprise was an enormous undertaking, with new quarries, roads, camps and all the rest of the paraphernalia of a major construction project being required.

We anchored off St. Mary’s within sight of the chapel with the plan to row ashore to visit it. However, the weather deteriorated to a thick scotch mist, stopping even the local dinghy sailors getting their evening race in the bay. We decide to visit tomorrow, shut the hatches and retire for the evening

Ship’s log

Day’s run: 25.8 nm

Total miles to date: 1397.8nm

Engine hours: 0.8 hours

Total engine hours: 167.4 hours

Hours sailed: 5.5 Hours

Total hours sailed; 313.2 hours

Wednesday 24th July – St. Margaret Hope, the Italian Chapel and the Churchill Barriers

Next morning we awoke to find the weather windy so we invoke Plan B which is to sail down to St. Margaret Hope on the island of South Ronaldsay where the pilot book reports that there is a pier we can tie up to. We duly sail in but find the pier has local boats tied up with the only free spot being under a drain pipe gushing water so after a phone call to the harbour master we end up anchoring in the bay out of the way of the fast catamaran ferry that operates to the mainland. However, it is sheltered and we are able to go ashore in the rubber dinghy.

Next morning we awoke to find the weather windy so we invoke Plan B which is to sail down to St. Margaret Hope on the island of South Ronaldsay where the pilot book reports that there is a pier we can tie up to. We duly sail in but find the pier has local boats tied up with the only free spot being under a drain pipe gushing water so after a phone call to the harbour master we end up anchoring in the bay out of the way of the fast catamaran ferry that operates to the mainland. However, it is sheltered and we are able to go ashore in the rubber dinghy.

St. Margaret Hope is named after Margaret, “Maid of Norway”, who died here aged 10 on her way to marry Edward II of England. The Orkneys were her dowry. By a complex set of circumstances too long to relate here (see Margaret, Maid of Norway for more information), the Orkneys were never returned to Norway, but came under the Scottish crown.

The actual village is pretty, with hanging baskets. We have to wait for the bus so refresh ourselves at the local café with Orkney crab sandwiches and tea – very British! The bus duly arrives and whisks us back north, over three of the four Churchill barriers to the Italian Chapel.

The Chapel exterior. The wayside shrine to the left is centred on a gift made in 1961 of Christ crucified from Domenica Chiocchetti’s home town of Moena to the people of Orkney with the cross and canopy made in Kirkwall.

The back ground to the construction of the Chapel is that the Italians working on the Barriers were housed in a series of camps on the adjacent islands, constructed from Nissen huts. Over a period of time they were permitted to make their camps more homely with a few leisure facilities. However, the HM Inspector of POW Camps noted that they lacked any sort of church, which was deeply felt by the Italians.

By good fortune, circumstances bought together a new Commandant of Camp 60 on the small island of Lamb Holm, Major T.P.Buckland, an enthusiastic padre, Father P. Gioacchino Giacobazzi and an artist named Domenico Chiocchetti. Chiocchetti had already constructed a memorial of St. George (the patron saint of soldiers) slaying the dragon made from concrete and barbed wire. In late 1943 two Nissan huts were made available to the POW’s; these were joined end to end to form a chapel and (initially) a school. With the commandant’s blessing, Chiocchetti was allowed to gather together a small group of artists and skilled tradesmen and set to work to build a sanctuary at one end of the hut furthest from the camp.

St. George slaying the dragon. Sculpted from barbed wire and concrete by Chiocchetti as a centre piece of POW Camp 60 (the camp having long ago been dismantled).

As he worked his imagination caught fire. Ideas flooded into this mind but he had to express them using the simplest of materials, often reclaimed scrap.

The altar and behind it Chiocchetti’s masterpiece depicting the Madonna and Child, painted from a miniature he carried with him throughout the war.

Originally just the chancel was to be made but as this was done the rest of the hut looked barren and ugly, so with help from the commandant further materials were found and the whole building was eventually beautified. The outside also received attention, with a concrete front added.

The chapel was finished just as the war ended. A promise was made to Chiocchetti that the Orkney Islanders would look after his beautiful chapel. The fame of the chapel spread across the Orkneys and the islanders started to visit it. Experts advised the owner of Lamb Holm, Sutherland Graeme, that the nature of the materials used made permanent preservation impossible. However, Mr Graeme formed a committee to help preserve the chapel and some repairs were done using the donations of visitors. The BBC became interested and broadcast a programme throughout Italy about it in 1959. Chiocchetti was traced to his home town of Moena, a village in the Dolomites. In March 1960 Chiocchetti and his wife were sponsored by the BBC to return to Orkney to restore the paintwork and chapel, which was followed by a service of re-dedication.

Before he left Orkney, Chiocchetti wrote a letter to the people of Orkney. He wrote “The chapel is yours – for you to love and preserve.” Since then the chapel has become one of the top 20 churches visited in the UK and money has been raised to ensure its preservation.

The chapel is truly remarkable and worth the effort of getting there. The photos tell the story better than words. The chapel and the statue of St. George are all that is left of Camp 60 – only the spiritual parts of the camp remain and none of the material parts.

We take our time in the Chapel, and then walk over to the Orkney Wine Company, a local family enterprise making and selling wines made from local fruit and flowers. We enjoy a little wine tasting and buy some little silver earrings for Yvonne depicting the Italian Chapel.

A memorial at the Chapel in the shape of the silhouette of Churchill with the names of the people who perished building the barriers.

We get chatting to the girls running the shop, both Orcadians. It seems that true Orcadians regard themselves as Orkney people, not Scots. They do not speak Gaelic on the islands and there are no dual language signs (unlike some parts of rural Scotland) but the local dialect is mixed in with many words of Norse origin. The issue of independence is not very popular here and the girls felt that people would generally vote against it. We shall see.

Churchill Barrier No. 1 between Lamb Holm and Mainland. The core structure of rock and infill is protected by a skin of concrete blocks laid randomly to break up the sea waves.

Remains of sunken block ship off Burra Island at Barrier No. 3. The block ships proved insufficient to protect the fleet, hence the barriers were built.

We find there is a gap in the bus timetable so we decide to start walking back to St. Margaret Hope, across the Churchill Barriers. This proves to be more interesting than might have been thought as there are display boards at each barrier describing how things were done plus some of the old block ships are clearly visible.

Eventually the bus time comes round so we hail the bus Orkney style at a suitable place (there being no bus stops) and ride the rest of the way back. Soon we are back on board Sundart after another full day.

After supper we check the weather forecasts and then plan the trip back across the Pentland Firth to the mainland, which will need an early start to catch the tides right. (The Pentland Firth has some of the strongest tides in the world, leading to strong overfalls and eddies when the tide is at full strength. We need to cross at the change of tide when the flows are minimal). We set the alarm and turn in.

Ship’s log

Day’s run: 7.7 nm

Total miles to date: 1405.9 nm

Engine hours: 0.8 hours

Total engine hours: 168.2 hours

Hours sailed: 2.0 Hours

Total hours sailed; 315.2 hours

A following wind and fair weather to you all.

Yvonne and John